Rugby's El Clásico

When FC Barcelona and Real Madrid were rivals on the rugby field.

Every season millions of fans watch FC Barcelona and Real Madrid compete in El Clásico.

The contests between La Liga’s two most successful teams have come to define Spanish football, and beyond that, the wider cultural contests within the country.

Regionalism vs centralism. Catalonia vs the Crown. The game is played within historic boundary lines painted centuries ago, which were often much bloodier than a box-score.

But in the 1920s, when las líneas blancas that are now permanently painted on the Iberian grass were still wet, this parochial proxy battle was competed on multiple fronts. Both Real and Barça were multi-sport associations. Cycling, water polo, fencing, tennis, and, in its earliest days, rugby.

So in another timeline, rather than featuring an international cast of Jude Bellingham, Lamine Yamal, Pedri, and Vinícius Júnior, El Clásico could have featured Antoine Dupont, Finn Russell, Henry Pollock, and Sacha Feinberg-Mngomezulu instead.

The cultural exchange between France and Spain’s respective Catalan regions resulted in the early introduction of rugby. Spanish students learned the game in Perpignan, and Toulouse and brought it back with them to Barcelona, Girona and Sant Boi de Llobregat.

Baldiri Aleu i Torres, a veterinarian who had worked in France, founded the first dedicated rugby club, Unió Esportiva Santboiana, in 1921. The sport soon spread to the more established regional clubs after Torres founded the Spanish Rugby Federation (FER) in 1922 and translated a rulebook, the Códic i Reglaments del joc de futbol-rugby, in 1925.

Rugby quickly became a cultural cornerstone, bolstered by regular visits from their cousins north of the Pyrenees. And FC Barcelona were soon their best exponents.

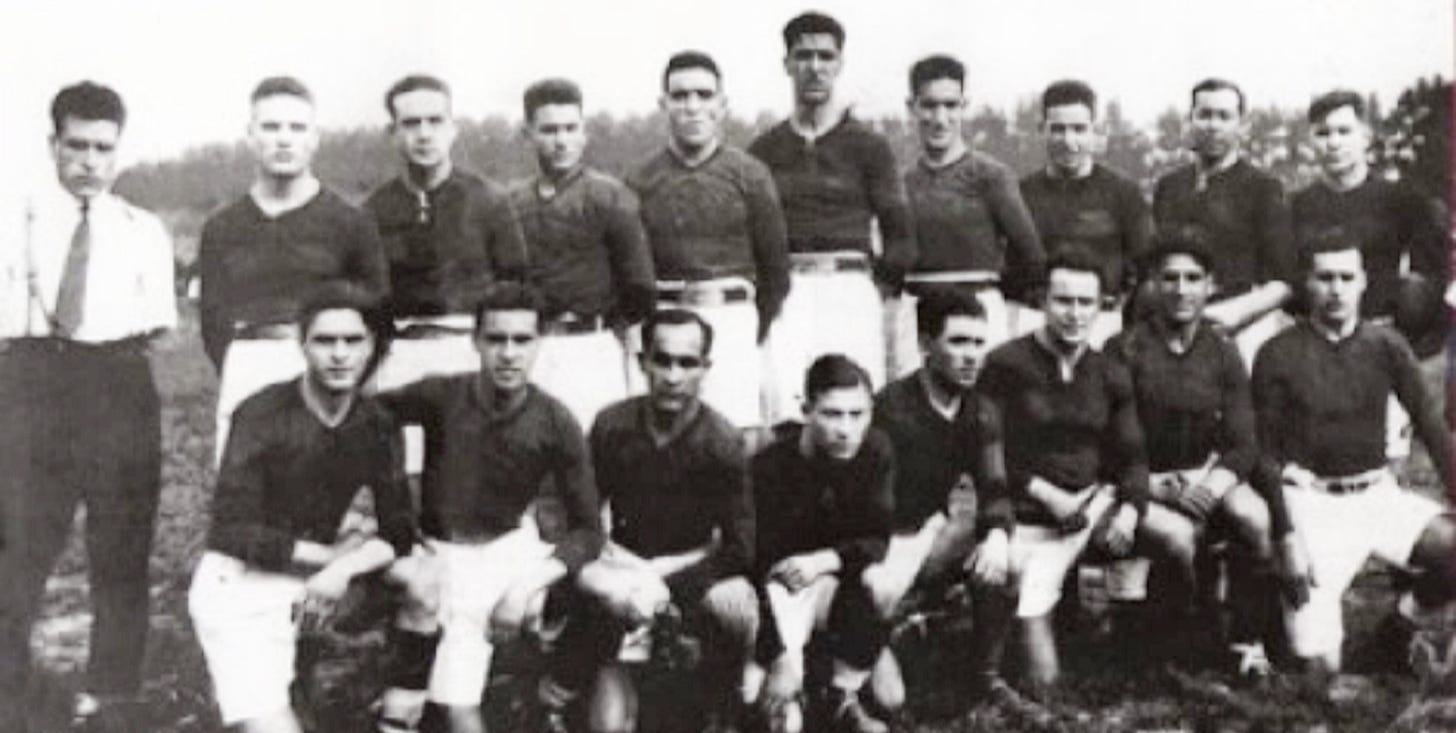

Already well-established in the capital, they had access to a grass field, Camp de Les Corts, which held 20,000 people. They received tours from English students, and a variety of clubs from south of France, including two championship sides in US Perpignan and Stade Toulousain. Their win against the White Devils of Perpignan was described in the press as an “eloquent and decisive demonstration of the formidable sporting value [of the Catalan race].”1

But they had yet to test themselves against intra-country competition. Inevitably, the sporting success in the north-east caught the attention of the Castile region as well.

Rugby arrived in Madrid slightly later than Barcelona. Rather than being an exchange from France, it was brought by English soldiers and already established expats. But it took off quickly after the Miguel Primo de Rivera dictatorship saw the sport as one that would help improve the nation in the mould of muscular Christianity. An oval-shaped tool to create a disciplined, vigorous, and unified Spanish identity.

To quote Football Rugby Reglamentom, a guide published by the military: “Rugby football, more than any other sporting game, precisely for being harder, educates the character, tempers the nervous system, fortifies the body and increases courage and makes the man determined and energetic”.

But although Real Madrid was the biggest sports club in the capital, it was slow to succeed. Military teams won the early Regional Championships of Centro, so when a Spanish Rugby Championship, contested by the winners of Catalan and Castile, was suggested in 1926, the pressure was put on CDA Infantería de Toledo instead.

FC Barcelona were the Catalan champions, and in the resulting fixture the soldiers barely got out of their foxholes. The Blaugrana bullied them, winning 19-0, a victory that was hailed in L’Esport Català as a triumph that “united the aspirations of all Catalans around a sporting supremacy”.

And they might have looked forward to repeating this scalping a year later, but institutional instability interfered.

Owing to its popularity, the Catalans had set up the first federation, the FER, in 1922. Naturally, the Madrid-based administrators sought to break this regional hegemony and move the FER’s headquarters to Madrid, in line with the centralist, “españolización” ideology of the dictatorship.

It came to a head when France wanted to hold an international in 1927. Naturally, they asked Madrid, who in turn requested clarification from Barcelona. When the FER failed to reply to requests, the Castilian Federation acted unilaterally to organise the international themselves, creating a rival national body called the Spanish Rugby Union (RUE).2

Both acronyms continued to assume authority for the next few years, but no championship was held. Matters weren’t helped by continued political pressure and persecution. The repression of Catalan flags, language and institutions, culminated in the exile of FC Barcelona president Joan Gamper following a 1925 incident at a football game in Les Corts when the national anthem was booed with Primo de Rivera in attendance.

But by 1930 the dictatorship was out, and the Castilians, realising that they had no way of challenging the Catalan dominance, extended an olive branch to open the sport back up. It was decided that regional tournaments would decide the finalists of the Campeonato de España, contested in a final at the end of the year.

But Real Madrid and Barça could only meet if both won their respective regions. Luckily, during this time both of the sides had started to become nationally known already as close competitors.

Football had established itself as the nation’s most popular sport. Spain had earned a silver medal in the 1920 Olympics, and the Primera Division, the league that would eventually become La Liga, had begun in 1929. In its inaugural season Barcelona had finished top and Real Madrid second in a final day finish that would eventually become familiar to fans.

Perhaps buoyed by this recent success with the rounder ball, both sides won their rugby regions in the 1930 season. And the final, the first El Clásico de Rugby, was set for June 24, 1930 at Barcelona’s Camp de Les Corts.

Reports said that Les Corts was “muy concurrido”, very crowded, for the final. Partly because it was the Diada de Sant Joan, the Catalan midsummer festival.

Against the backdrop of bonfires, music and fireworks, Barcelonins would have wandered from the city out towards the suburban stadium in the late afternoon. On each avenue the smells shifted from gunpowder and burning crates to sardines cooking and oil heating in open kitchens.

Stood in the terraces the 20,000 fans ate fresh flatbreads topped with fruit, nuts and custard, the haze from the smoke trapping the heat in their shirts on the already hot June day.

The festival flair might have taken the visiting Madrid players off guard. The shouts of “Som-hi!” from the crowd punctuating the explosions in the air, the city full and on fire, reminded them this was an away fixture, in a foreign country.

In the first half, Real Madrid put up a fight. The home side had a “ligero dominio” (slight edge) but the contest was relatively even through forty minutes. Barcelona racked up a 14–5 lead by the break.

But by the second half, Real Madrid’s players appeared exhausted.

The Catalans took full control, showcasing their better conditioning and cohesion from having played a more competitive league in the previous half a decade.

They ran in five tries in the second period while Real Madrid failed to score again. The final result was a 39-5 victory, and Barcelona became Spanish champions for the second time.

Sources from the time said that Real Madrid was hindered by only having played “six games all year”3, whilst FC Barcelona benefited from a robust and “highly active” schedule of domestic championships, plus visiting games from Perpignan and Toulouse during the dormant years of the championship.

But it was a comfortable win, and confirmed that “the hegemony of Catalan rugby was not in doubt”.

After this first meeting, a resolute Real Madrid became the dominant force in Castilian rugby. They reached the final again a year later, losing again to the Catalans, this time UE Santboiana, 12-6. A year Los Blancos played Barcelona again, this time losing in Madrid 20-3.

In three attempts, they couldn’t conquer the Catalans, and in 1934 they lost the chance to compete against them for good.

In 1934 a rival to England’s RFU, the International Amateur Rugby Federation (FIRA), was founded in Paris by France, Italy, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania and, crucially, Catalonia.

The Spanish Federation in Madrid was apoplectic, and promptly expelled the rebel region from national competitions. Catalonia, now a full member of the FIRA, continued to organise a domestic tournament and various official selection matches against France and Italy, but the Spanish championship would now be competed by the other regions.

Which is how Real Madrid won their first title, beating a team made up of Valencian students 14-6 in the 1934 Spanish Championship. It would prove to be their only ever title.

Two years later the Spanish Civil War started, and the lines that were drawn on the fields became entangled in barbed wire. There was little sport, and Barcelona bore the brunt of the bans. The team and its colours were banned, Les Corts became a refuge for the region, and rugby stopped entirely.

Rugby would return in 1941, now competing for the recently renamed Copa del Generalísimo. But the collective psyche of the Spanish people, fractured further by war, only had space for one code to survive. Resources, prestige, and political capital flowed one way in Francoist Spain, towards association football.

Real Madrid closed their rugby chapter in 1948, and with that the chance of any further El Clásico games. FC Barcelona on the other hand continued to play, and became one of the more successful franchises in the history of Spanish rugby. They celebrated their centenary in 1924, and won the championship in 1952 and a cup in 1985.

FC Barcelona and Real Madrid are two of the biggest sporting institutions in the world, just not in rugby. There was a brief rivalry, an El Clásiquito and quirk of trivia, but history, football, and fate interfered.

Still, the game spread beyond the myopic borders of Catalonia-Castile. There’s a robust national league, with over 35,000 male and female registered players playing for more than 300 clubs. After a few false starts, the men’s national team recently qualified for the 2027 Rugby World Cup, their first since 1999.

And Spanish rugby does have its own El Clásico.

The biggest rivalry is contested by Valladolid RAC and CR El Salvador. They both share a stadium, Estadio Pepe Rojo, on the outskirts of Valladolid in Castile & León. It’s a cross-town derby, with the two clubs winning 17 of the last 20 División de Honor de Rugby titles4.

Besides, big names don’t always make big rivalries. There’s a lot of competitive rugby in Spain in the present day, so if you want to find rugby’s El Clásico, look beyond the Barça-Real binary, and take a trip to the centre of the country instead.5

Though it was played, and resulted in a 66-6 loss, to this day it's considered unofficial.

That and bizarrely a regional game between Catalan and Centro was played a few days before. It featured nine from Madrid and four from Barcelona, contributing to the tiredness.

Valladolid have won 12, El Salvador 5.

Sources: Beginnings and Development of Rugby in Spain, Carlos Castellar and Francisco Pradas, Physical education and sport through the centuries (2021), The Origins of Rugby in Catalonia, Mariano Pasarello Clerice and Marc Sentís Sabaté, Physical education and sport through the centuries (2021)La historia del rugby en España. 1ª parte. De los inicios del juego hasta 1923 & La historia del Rugby en España, IIª Parte. De 1924 hasta la II República, Xavier Torrebadella-Flix, Revista de Ciencias del Deporte (2024).